Alan's work in Depeche Mode

List of DM songs written by Alan- Two Minute Warning

- The Landscape Is Changing

- Fools

- If You Want

- In Your Memory

List of DM songs co-written by Alan (with Martin Lee Gore)

- The Great Outdoors

- Work Hard

- Christmas Island

- Black Day

- Stjarna

Others

- Alan also performs Beethoven's "Sonata No. 14 in C#m (Moonlight Sonata)"

WORK HARD

The same week as Vince's departure was announced to a

shocked music press, a classified advertisement appeared in the back pages of Melody

maker: "Name band, Synthesizer, Must be Under 21." Applicants would be told

everything else later on - who the "name band" was, of course, but also that

there would be no recording work, no chance of advancement, maybe even nothing more than a

few gigs in America in march 1982.

The same week as Vince's departure was announced to a

shocked music press, a classified advertisement appeared in the back pages of Melody

maker: "Name band, Synthesizer, Must be Under 21." Applicants would be told

everything else later on - who the "name band" was, of course, but also that

there would be no recording work, no chance of advancement, maybe even nothing more than a

few gigs in America in march 1982.

But even as they awaited the first responses to their classified ad, the band remained adamant. They would not take the first remotely capable idiot to walk through the door; they would not be rushed or bullied into making a decision. Whether the new boy stayed for six weeks or six months, he had to be someone they could live with - and who could live with them.

Alan Wilder was one of the few who fit neither stereotype. He could play synthesizer, of course, together with virtually every other keyboard instrument Depeche Mode cared to mention. But when they introduced him to their repertoire, he simply looked politely curious. ”I’d heard of Depeche Mode,” he admits, ”but I hadn’t actually heard any of their songs. I wasn’t that interested in the group at that time.”

He wasn’t under twenty-one, either. Born on June 1, 1959, Alan was a full

year older than anyone else in the band. But he was willing to lie if it meant a new

challenge.

He wasn’t under twenty-one, either. Born on June 1, 1959, Alan was a full

year older than anyone else in the band. But he was willing to lie if it meant a new

challenge.

Alan came from the occasionally affluent middleclass suburb of Acton, in west London. Like his two older brothers, he had a strong musical background; his parents had insisted on classical piano lessons for their youngest son, although when Alan left school in 1975, his abilities counted for little at his first job - making tea at a small central London recording studio.

Alan didn’t mind. His ambition was to become a studio engineer, but he didn’t hide his musical abilities, particularly once he realized that he was a considerably more accomplished pianist than many of the musicians who passed through the studio. Before long, Alan was appearing as an uncredited studio musician on a variety of recordings, and finally, he bowed to the inevitable. Accepting that ”I was spending more time helping out on sessions as a keyboard player than doing anything in the control room,” he decided to throw himself into full-time musicianship.

None of Alan’s early bands did anything: not the soft-rock Dragons, who worked the west London youth-club circuit; not Reel to Reel, who remained similarly locked to the local pub scene; not even Daphne and the Tenderspots, a vaguely New Wave-ish band that even released a single, the novelty-tinged ”Disco Hell”.

It all counted as experience, however, and toward the end of 1981, Alan answered a Keyboards Wanted ad placed by the Hitmen, a once highly rated band that had emerged toward the end of the 1970s, in the hope that amid the manifold themes and streams being thrown at the pop market, theirs might be the one that would stick.

It was not to be; guitar bands - as Gary Numan had proved - were out, and the Hitmen (whose brilliant young lead player, Pete Glenister, now records and tours with Kirsty MacColl) were no exception.

Desperate to move with the times, the Hitmen augmented their lineup with a synthesizer, just in time for their second album, Torn Together. It didn’t help, and by the time Alan joined, the Hitmen’s lineup had been pared to a minimal three-piece - Glenister, vocalist Ben Watkins, and drommer Mike Gaffey. Their recording contract with CBS was nearing an end; the band members’ own patience was similarly fraying.

”Ouija,” the band’s final single, was recorded without either Alan or the similarly newly-recruited bassist John Jay (from Depeche Mode’s Bridgehouse contemporaries, the Ian Mitchell band) taking part, and the pair had played no more than handful of live shows with the band when Alan spotted that fateful ad in Melody Maker.

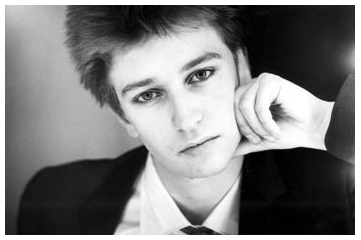

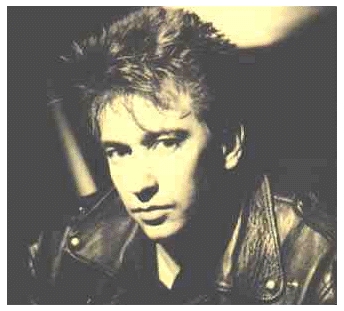

Later, Dave would joke that Alan Wilder looked more like a ”real rock

star” than anybody else in Depeche Mode. His short hair straggled spikily, his gaunt

face bristled with a light stubble forced out by sharp cheekbones, and he arrived at the

audition clad in a leather jacked and jeans. He looked odd standing behind a synthesizer;

with looks like his, he should have been a guitarist, his instrument slung around his

knees, furiously exorcising the Keith Richards - shaped demons that had so obviously

determined his appearance.

Later, Dave would joke that Alan Wilder looked more like a ”real rock

star” than anybody else in Depeche Mode. His short hair straggled spikily, his gaunt

face bristled with a light stubble forced out by sharp cheekbones, and he arrived at the

audition clad in a leather jacked and jeans. He looked odd standing behind a synthesizer;

with looks like his, he should have been a guitarist, his instrument slung around his

knees, furiously exorcising the Keith Richards - shaped demons that had so obviously

determined his appearance.

But he only needed to hear a melody once before he was playing it, even improving upom it. When Martin, Dave, and Fletch agreed to affer Alan a place in the band, Dave joked that if it didn’t work out, he could have their jobs as well.

The group offered Alan the most generous terms they could - a six-month trial basis that would see them through to the recording of their second album. In the meantime, he would be starting work immediately, as Depeche Mode set about promoting their first post-Vince single, Martin’s ”See You”.

Strangely, the ambivalence that Depeche Mode wore

when they faced the outside world was not altogether a simple brave front. For all their

resentment and fears, and the awkwardness that was to sour the band members’ future

personal relations with the errant Vince, confidence within the band was high -

particularly after Alan announced that he, too, could write songs.

Strangely, the ambivalence that Depeche Mode wore

when they faced the outside world was not altogether a simple brave front. For all their

resentment and fears, and the awkwardness that was to sour the band members’ future

personal relations with the errant Vince, confidence within the band was high -

particularly after Alan announced that he, too, could write songs.

Alan Wilder’s six-month trial period was due to end shortly before Depeche Mode returned to the Blackwing studio to begin work on their second album - refreshed after taking their first proper holidays in almost two yers.

Music, on the other hand, was all Alan thought about, and when Depeche Mode reconvened at the end of July 1982, they were as conscious of his single-mindedness as anybody could be.

Unlike many of the bands whose live show relies on prerecorded tapes, Depeche Mode was never content to simply adapt their studio recordings to the new environment. Rather, they would laboriously rerecord their backing tracks, exaggerating certain elements of the original version, playing down others. It was - and remains - a time-consuming exercise, especially as the band members took it seriously, it was not one of their favorite chores.

Alan, however, delighted in the task. Even today, his

bandmates describe him as the only truly musical member of the group, and his talent and

enthusiasm even resounded through the tapes he prepared from the band’s Speak And Spell

material. Long before Martin, Dave, and Fletch informed him that they wanted him to remain

with the group on a permanent basis, at the end of July, Alan was fairly certain he’d

gotten the job. Which made the band’s next decision all the harder for him to také and,

perhaps, for them to deliver.

Alan, however, delighted in the task. Even today, his

bandmates describe him as the only truly musical member of the group, and his talent and

enthusiasm even resounded through the tapes he prepared from the band’s Speak And Spell

material. Long before Martin, Dave, and Fletch informed him that they wanted him to remain

with the group on a permanent basis, at the end of July, Alan was fairly certain he’d

gotten the job. Which made the band’s next decision all the harder for him to také and,

perhaps, for them to deliver.

Alan had been wondering why no one had yet given him the precise details of the upcoming studio sessions, but convincing himself that the others simply assumed he knew, he waited until virtually the last minute before asking what time he should turn up at Blackwing.

Martin shuffled his feet awkwardly. ”Actually, you don’t really have to.” ”What’s that supposed to mean?” ”We won’t be needing you. We don’t want you to record with us.” Fletch chimed in. ”Or to tell anyone you’ve joined the group properly.” They tried to explain; they still weren’t yet ready to fully open their ranks to the newcomer. Although Alan was welcome to drop by the studio to watch, his presence as a musician was not required.

Alan was furious. ”I thought we’d got over that! You’ve only just asked me to join the band - are you kicking me out agin already?” ”It’s not that…” Fletch, Dave, and Martin looked uncomfortable, but they were determined all the same. Patiently, they explained that despite ”See You,” despite their live successes, Depeche Mode still had something to prove - to themselves, and to ”all the people out there who still reckon Vince was the brains behind the group.”

"If the world stopped spending all the money it spends on arms for just two weeks, you could feed the starving millions for two years."

Introducing Alan into the studio would simply allow their detractors even

more ammunition, ”like we couldn’t cut it on our own, so we had to bring someone else

in, a proper musician” - the only one in the group. They were determined that no one

would ever have the opportunity to accuse them of that.

Introducing Alan into the studio would simply allow their detractors even

more ammunition, ”like we couldn’t cut it on our own, so we had to bring someone else

in, a proper musician” - the only one in the group. They were determined that no one

would ever have the opportunity to accuse them of that.

Alan was scarcely able to conceal his rage, but he accepted the band’s will, even went along with them when they asked that he keep his full-time recruitment in the group a close secret. But he swore that it would be different next time.

Shortly before Christams 1982, a Mute press release announced that Alan was joining Depeche Mode as a full member. He would be making his recorded debut in the new year, with the band’s nex single, ”Get the Balance Right”; not only that, but he would also make his first appearance as martin’s songwritting partner - the instrumental b-side, ”The Great Outdoors,” was a joint Wilder-Gore composition. The possibility that without these concessions Alan might have simply quit the group in frustration was not acknowledged.

In print, Alan took his lengthy apprenticeship lightly. ”I was touring and doing TV with them, but ... somebody in their position doesn’t bring in somebody new in the first week who might turn out to be a complete arsehole.” having proven that he wasn’t that, he said with a smile, it was only natural that he would eventually take his place in the group. The lie rankled, but it was finally at an end. The expertise that Alan had already brought to Depeche Mode’s live sound could now explode in the studio.

”When we first ordered the Synclavier,” Daniel Miller remembered, ”we

already knew all about it and had loads of ideas as to what we could do with it.” One of

those ideas involved exploring what Miller calls ”the psychological effect of recording

sound in their own acoustical space, and using them without adding any artificial

reverb.”

”When we first ordered the Synclavier,” Daniel Miller remembered, ”we

already knew all about it and had loads of ideas as to what we could do with it.” One of

those ideas involved exploring what Miller calls ”the psychological effect of recording

sound in their own acoustical space, and using them without adding any artificial

reverb.”

Frequently he led the band outside the studio, to tour London’s East End in search of new sounds to sample. Neighborhood construction sites fast proved a particularly fruitful hunting ground. On one occasion, the band was happily recording the sound of things banged against a fence when an overvigilant watchman burst onto the scene. The ensuing sound, according to Alan, went ‘CREEESH-OY!”

”One day,” Miller explains, ”we grabbed a stereo tape recorder and sampled a bunch of things - old metal, botles breaking, things running into walls - then brought the sound back to the studio and put them into the Synclavier.”

”You can take the purest voice in the world,” Alan enthused, ”and fool around with it digitally until it’s the most monstrous, evil sound. Or you can také a moose fart and make it beautiful.”

Work on what was to become Construction Time Again - a name suggested by the industrial clattering of so many of the tracks - stretched throughout the spring and early summer of 19893, with the first weeks spent collecting samples, building up a library of sound to which the band could refer during the actual recording process.

”But not to destroy,” Alan explained. ”Because

he’s a worker, it’s to rebuild it - it’s positive. That was the overall idea of the

album, to be positive.” That, he continued, was why the band chose the title

Construction Time Again, ”not Destruction.”

”But not to destroy,” Alan explained. ”Because

he’s a worker, it’s to rebuild it - it’s positive. That was the overall idea of the

album, to be positive.” That, he continued, was why the band chose the title

Construction Time Again, ”not Destruction.”

The image of the worker was a loaded one, nevertheless, redolent of socialism, even - in a Britain four years into Margaret Thatcher’s belligerently capitalist rule - communism. In any other society, Martin and Alan’s mantric ”Work Hard” would have been regarded as a shining example to a work-shy youth. In Britain in 1983, it was described as a left-wing manifesto - a frightening preconception in an increasingly frightening country.

Construction Time Again shattered that vow. ”When we decided on the theme for the album,” Alan informed NME writer X. Moore (himself a member of the socialist band the Redskins), ”the first word that came up was ‘caring,’ and that’s the main behind it.”

The Musicians’ Union itself took a firm stance behind the traditionalists. Among the many samples Depeche Mode intended using on their forthcoming album were a series of percussive notes that they obtained by inviting a noted drum collector along to the studio and having him play a single beat on each one.

”There’s no doubt that he understood what we were

doing,” Alan complained. ”Then he sent us a bill for sampling fee, consultancy fee -

God knows what else. He’d been talking to the MU, who’d obviously convinced him that

what we were doing was totally immoral, and he charged us six times the amount we’d

agreed.”

”There’s no doubt that he understood what we were

doing,” Alan complained. ”Then he sent us a bill for sampling fee, consultancy fee -

God knows what else. He’d been talking to the MU, who’d obviously convinced him that

what we were doing was totally immoral, and he charged us six times the amount we’d

agreed.”

With the self-righteous shortsightedness of the true acolyte, Martin and Alan furiously defended Depeche Mode’s use of sampling - and everybody else’s. ”We’d be quite happy for people to nick our sounds and sample them.” Alan admitted that Depeche Mode had already lifted a drum beat from a Frankie Goes To Hollywood single, and added it to one of their recent twelve-inch remixes.

”I don’t think you can stand in the way of technology - you’ve just got to have the ideas and the imagination to put it to original use.”

And even better was to come. ”People Are People” was among several tapes Depeche Mode handed to producer Adrian Sherwood so that he might remix them in his own inimitable fashion. (”Just Can’t Get Enough,” ”Photographic’” and an unreleased track called ”Death Wish” were also included.) The ensuing twelve-inch singles defied even Depeche Mode’s reputation for adventure.

”We made a conscious decision to become harder

musically,” Alan explained to Record Mirror.

”We made a conscious decision to become harder

musically,” Alan explained to Record Mirror.

But if ”People Are People” was surprising, its B-side, Alan’s ”In Your Memory,” was even more so. Its harsh melody line was almost theoretical, carried wholly by Dave’s voice in strict opposition to the direction taken by the backing track.

A study of sexual domination, twisting from bedroom to boardroom, ”Master And Servant” rode in on an a cappella falsetto, as breezy as any intro in Depeche Mode canon. Discussing Depeche Mode’s first attempts to break the teenybop mold, Alan admitted that ”we’re in the position where we know we’re going to get a certain amount of airplay just on the strenght of reputation,” and although neither Depeche Mode nor Mute had any compunction whatsoever about releasing ”Master And Servant” as a single, the day that the BBC’s Radio One called the office demanding a copy of the lyrics was a fraught one.

Some Great Reward was the first album the band members were unanimously

”really proud of.” SGR remains the first true Depeche Mode album - the first on which

the band had fully absorbed the experiences and experiments that, on earlier recordings,

were obviously as novel to them as they were to the audience.

Some Great Reward was the first album the band members were unanimously

”really proud of.” SGR remains the first true Depeche Mode album - the first on which

the band had fully absorbed the experiences and experiments that, on earlier recordings,

were obviously as novel to them as they were to the audience.

Depeche Mode visited a lot of customs halls as 1984-85 unfolded. They had, to their not-altogether-concealed disgust, settled comfortably into the single-album-tour-new-single routine, the lot of every band whose appeal was now too great for them to still be struggling, but still too small for them to start taking interminable breaks between records.

Another new single, the gorgeous ”It’s Called A Heart,” followed ”Shake The Disease” onto the album; again, it was a lesser hit than it deserved to be, but that, at lesat, was understandable. It was released within a month of its appearance on the album, too soon even for its ultimate chart position to be included within the compilation album’s sleeve notes, and with The Singles 1981-85 (retitled Catching Up With Depeche Mode in America) rapidly sharping up as one of the year’s most popular stocking fillers, who could blame the public if they did not buy the same song twice in one week?

Black Celebration was never going to be an easy album to make. As usual, Martin had a very fixed idea of how he wanted the new record to sound, but his muse was apparently working in direct opposition to his dreams. The rest of the band’s ideas, too, were often at violent odds with Martin’s.

The problem was, as the four-month-long recording

process stretched on into the spring of 1986, it was not only ideas that were sailing into

oblivion. Depeche Mode’s very fabric was beginning to tear. Alan was unable even to

recollect any frictions beyond ”the problems … all groups have.” ”If we were ever

going to break up the band,” dave warned, ”it would have happened then.”

The problem was, as the four-month-long recording

process stretched on into the spring of 1986, it was not only ideas that were sailing into

oblivion. Depeche Mode’s very fabric was beginning to tear. Alan was unable even to

recollect any frictions beyond ”the problems … all groups have.” ”If we were ever

going to break up the band,” dave warned, ”it would have happened then.”

”We started rationalizing,” Alan admitted; having progressed, as journalist Danny Kelly put it, ”from A somewhere past C,” did the band need to continue on to points D, E, and F in that order? Or could they leap illogically on to point J or even L, and hope to také their audience with them?

For Depeche Mode ”Route 66” marked a critical juncture in their development, that at which they finally crossed the Rubicon upon whose banks they had halted so many times in the past. For it was one thing for Martin to wear an acoustic guitar on stage, unplugged and unplayed, for the benefits of the TV cameras. But it was something else entirely for Martin to enter a recording studio, set the tapes rolling, then strike that first resounding guitar chord, and to keep striking until the whole performance was captured forever.

”We don’t think of ourselves as a keyboard band at all,” Alan explained patiently, and for the umpteenth time, as Depeche Mode ran the gauntlet of American interviews. ”We like to consider sound itself as our only restriction. We work within the practicalities of what we do, and most of the time that tends to involve keyboards, rather than play them live. Because it’s a bit easier for us to work that way.”

According, again, to Fletch, ”We feel we do our

best when we’re all working on the songs together, right from the beginning.” Music

for the Masses left no room for musical maneuvering, few places in which even Alan, the

musical dynamo of the group, could insert the independent inventiveness that led songs

away on a whole new tangent.

According, again, to Fletch, ”We feel we do our

best when we’re all working on the songs together, right from the beginning.” Music

for the Masses left no room for musical maneuvering, few places in which even Alan, the

musical dynamo of the group, could insert the independent inventiveness that led songs

away on a whole new tangent.

”We’ve sampled a pygmy doing his wail, but we’ve turned that into something that sounds nothing like a pigmy,” laughed Alan. ”We also do a lot of reversing and looping, so by the time you’ve used a sound, like a loon on ‘Strangelove,’ you sometimes can’t remember what it was when you started.”

Released in August 1987, ”Never Let Me Down Again” was, in many ways, the most typical Depeche Mode song on the forthcoming Music for the Masses album. Elsewhere, it was suggested that Martin wrote the song either or about Marc Almond - the song’s coda was practically identical to the chorus of Soft Cell’s now five-year-old ”Torch.” ”But that’s one of the nicest things about Martin’s words,” Alan countered. ”The fact that they can mean different things to different people, depending on how people decide to interpret them.” (”the travelogue becomes a metaphor for drugs or gay sex,” growled New York’s Village Voice).

It was, then, something of a relief when the band scored a totally unexpected British hit with ”Little 15,” a single released in Germany alone, but imported into Britain in such quantities that it actually charted! Music for the Masses itself had struggled to reach the U.K. Top Ten, and while ”Little 15” scraped no higher than number sixty, only Cliff Richard in 1961, and the Jam had previously scored so high with a foreign release.

”I think the problem [in Britain] is very much due to the people who control the BBC,” Alan explained in America. ”Because the BBC controls all the major television and radio, the BBC producers decide what people will listen to.” Depeche Mode was still granted ”a certain amount of hearing” because of their track record, ”and because we have this hard-core following that demands it. But the BBC producers play our songs reluctantly - they’d rather not, but they have to.”

The original title for Pennebaker’s Rose Bowl movie was A Brief Period Of Rejoicing. Within weeks, however, that title was dropped in favor of the more prosaic 101 - the Rose Bowl had been the 101st concert of the Music for the Masses tour. ”We’d never go for shock’s sake,” Alan once remarked. ”But there’s a certain edge to what we do that can make people think twice about things.” More than a month before the show, Rose Bowl ticket sales had topped 53.000; the final total of 66.233 represented a 95 percent sellout of the enormous stadium.

”We’d like to think that in the future, people will look back and see us as having made some sort of forward step,” said Alan. That’ he presumed, was the original concept for 101 ”the Eighties, and how we fit into the decade. We really wanted to explore why we were so indicative of the Eighties, as opposed to earlier decades.” Pennebaker dismissed Alan’s vision, but argued that what 101 captured was of considerably greater importance. ‘I think Alan imagined we were going to interview a lot of people, and out of that, the band, would find something that would beguile them. They’ve [the band] really though a lot about the music; they know the words and are right into it. For the band, this must be a kind of wonder. They’re not all that old, they haven’t thought this through philosophically. Alan is probably the most intellectual of the four, and he was hoping that we’d find some kind of answer.”

The first bricks flew a little after ten p.m. For the

past hour, the police had been trying to maintain some order to a line that had been

growing for forty-eight hours now, and stretched for close to fifteen blocks. But even

with riotready reinforcements arriving throughout the evening, a crowd of almost ten

thousand people was simply too overwhelming. Streets away, passersby marveled

incredulously at the scene, and their murmuring could be heard throughout Los Angeles. It

was March 20, 1990, and Depeche Mode was in town, signing copies of their new album at a

La Cienega Boulevard record store.

The first bricks flew a little after ten p.m. For the

past hour, the police had been trying to maintain some order to a line that had been

growing for forty-eight hours now, and stretched for close to fifteen blocks. But even

with riotready reinforcements arriving throughout the evening, a crowd of almost ten

thousand people was simply too overwhelming. Streets away, passersby marveled

incredulously at the scene, and their murmuring could be heard throughout Los Angeles. It

was March 20, 1990, and Depeche Mode was in town, signing copies of their new album at a

La Cienega Boulevard record store.

Depeche Mode reached the Wherehouse exactly on schedule, a little before nine p.m. There was a sense of expectation in the air, a sense not of simple longing, but of emotional, sexual, cultural, explosive longing. Later, L.A. police captain Keith Bushey admitted that something had to give. "You can't put that many people in that small an area without something [happening]." And when it did happen, he didn't blame the crowd. They were, he assured the media, "really good, solid young people. There was no evil intention on anybody's part." He sounded almost helpless as he added, "There was just so many of them."

Depeche Mode themselves put a brave face on the incident. ”As bad and as dangerous as the situation was,” Alan candidly commented, ”it was good PR. We were in the news all across the country.” Sitting back at their hotel, with every news station reporting how ”English pop group Depeche Mode brought traffic to a standstill,” they found it difficult to hide their jubilation - even more difficult than it was to pretend that Depeche Mode was not at last living out their ultimate pop fantasies.

It was, all things considered, a suitably apocalyptic welcome for a band

whose latest American album was called Violator.

It was, all things considered, a suitably apocalyptic welcome for a band

whose latest American album was called Violator.

Depeche Mode was still in the studio when "Personal Jesus" was released in August 1989. They had thirteen songs programmed into the computers-as usual, everything was written and demo-ed long before any studio time was booked, and at that early stage, thoughts turned not only toward a full-length album, but also to an EP of material that Fletch described as "pretty interesting and quite apart from the normal stuff we do."

Happily, Alan admitted that "I didn't know how anything would end up until I was finished." ldeas would be followed to their ultimate musical conclusion, then scrapped or retained as Alan saw fit. Starting from a single sequence, "a bass line or some kind of mid-range part," he would "let it play around, let myself be hypnotized, and then see where that led me."

Like Music for the Masses, the new Depeche Mode album was pieced together in new surroundings, with a new producer, Mark "Flood" Ellis, and a legendary mixer, Francois Kervorkian, the New York-based producer.

The sessions themselves shifted between Milan's Logic Studios, Axis in New York, London's Church and Master Rock studios, and the Danish Puk complex, where Music for the Masses was mixed.

As usual, the album boasted its fair share of private jokes. The title itself

was chosen because the band wanted a name that sounded like it belonged on either a

heavy-metal disc… or a hardcore porn book. Violator fit both bills. One track,

"World in My Eyes," borrowed its title from fellow Mute artist Loop's album

World in Your Eyes. Elsewhere, responding to the escalating percentage of reviewers who

labeled Depeche Mode the "new Pink Floyd," one trackthe moody "Clean"

finale-lifted its opening bass line almost directly from the Floyd's own "One of

These Days."

As usual, the album boasted its fair share of private jokes. The title itself

was chosen because the band wanted a name that sounded like it belonged on either a

heavy-metal disc… or a hardcore porn book. Violator fit both bills. One track,

"World in My Eyes," borrowed its title from fellow Mute artist Loop's album

World in Your Eyes. Elsewhere, responding to the escalating percentage of reviewers who

labeled Depeche Mode the "new Pink Floyd," one trackthe moody "Clean"

finale-lifted its opening bass line almost directly from the Floyd's own "One of

These Days."

"Personal Jesus" was not an assault on religion, even if there was something mildly disturbing about a seductively choppy blues tune that recommended its listeners pick up the telephone and win instant conversion. According to Martin himself, the song was actually based upon Priscilla Presley's portrait of her late ex-husband in the book Elvis and Me.

Although it was to take six months to register on the Billboard Top Forty,

"Personal Jesus" entered immediately into heavy airplay on MTV, its stunning

video (situated to southwestern sleazy desert bordello) directed again by Anton Corbijn,

and excerpted from another mini-movie, Strange Too.

Although it was to take six months to register on the Billboard Top Forty,

"Personal Jesus" entered immediately into heavy airplay on MTV, its stunning

video (situated to southwestern sleazy desert bordello) directed again by Anton Corbijn,

and excerpted from another mini-movie, Strange Too.

Depeche Mode themselves acknowledged this influence when Alan grafted a housey beat onto Martin's original, organ-powered, vision of "Enjoy the Silence.

But the band was not to escape the fallout from so shocking an event.

According to Rolling Stone, one Los Angeles venue had ”expressed reservations about

booking the band on its upcoming U.S. tour.” The tour was to be part of Depeche Mode’s

longest ever, a worldwide outing that would keep the group on the road well into 1991.

But the band was not to escape the fallout from so shocking an event.

According to Rolling Stone, one Los Angeles venue had ”expressed reservations about

booking the band on its upcoming U.S. tour.” The tour was to be part of Depeche Mode’s

longest ever, a worldwide outing that would keep the group on the road well into 1991.

As fast as ticket offices opened, the demand swamped them. In New York, Depeche Mode sold forty-two thousand tickets for their Giants stadium show within a day. Dallas’s twenty thousand-seat Starplex Amphitheater was sold out within a week; so was the World Music Theater in Tinley Park, Chicago. In Los Angeles, where the now traditional tour closer was to take place, forty-eight thousand tickets for the August 4 show at Dodger Stadium were sold within an hour of going on sale, two months before the gig. Within seventy-two hours, a second night was added - and that sold out even faster. Even in Florida, there was a volley of four sold-out gigs.

When Violator was released that same month, it shipped gold. Dave was

cracking under the pressure, but all three of his bandmates had noticed that he was

changing. Irritable, even irascible, he had apparently stopped enjoying himself, on- and

offstage. He snapped when he was questioned, barked demands where once he would have

offered suggestions.

When Violator was released that same month, it shipped gold. Dave was

cracking under the pressure, but all three of his bandmates had noticed that he was

changing. Irritable, even irascible, he had apparently stopped enjoying himself, on- and

offstage. He snapped when he was questioned, barked demands where once he would have

offered suggestions.

Dave packed a suitcase and flew to Los Angeles. Alone. He and Joanne had been together since their teens, ”and we used to be really good friends. That had deteriorated, mostly on my part. You tug away until you lead separate lives. I decided the only way I was going to get a focus on my life was to crush everything down. I had to regain perspective on what I really wanted to do.”

The ill-fitting beginnings of a goatee beard sprouted on his chin. His flesh

was constantly raw from the fallout of his visits to what Alternative Press called ”some

truly brutal tattoo parlors.” His once-broad Essex accent now grated against the slang

Los Angeles colloquialismus that incongruously peppered his speech.

The ill-fitting beginnings of a goatee beard sprouted on his chin. His flesh

was constantly raw from the fallout of his visits to what Alternative Press called ”some

truly brutal tattoo parlors.” His once-broad Essex accent now grated against the slang

Los Angeles colloquialismus that incongruously peppered his speech.

He was found again by Teresa Conroy (often introduced as Conway), Depeche Mode’s press officer throughout their 1988 American tour, now working for the Triad booking agency. Through her, he would see the world - or, at least, the world according to L.A.

"I was like, `I fucking do that! I can do that!' " Dave still roars with excitement as he talks of his musical rebirth, the abrupt, shattering realization that whatever he may have represented in the past, whatever he could be in the future, right now he was a rock 'n' roll singer. All he needed now was to put a rock 'n' roll band behind him.

At the back of his mind, Dave was already half-convinced that maybe Depeche Mode had made the right decision when they parted company at the conclusion of the Violator tour with barely a backward glance. He was still proud of all the band had accomplished, but it all seemed so long ago right now, a different life, a different Dave Gahan.

The new buzzword was "alternative rock," and Dave grasped the concept by the horns. He wondered how the rest of Depeche Mode would react to it "I'm not saying I listen to better music than anyone else," he said with a sigh, "but I like seeing a lot of new bands." The first time he'd mentioned Rage Against the Machine to Alan, Alan's response had been, "Who?" "Get a clue, man!" And if Martin even suggested that Depeche Mode reconvene to make another dance album -"I probably wouldn't . . . bother making another record with Depeche Mode.

When, just after Christmas 1991, Martin called Dave

in Los Angeles to announce that he had another album's worth of songs demo-ed up, Dave's

first thought was to tell him to find another singer. Instead, he told him to send the

tapes over.

When, just after Christmas 1991, Martin called Dave

in Los Angeles to announce that he had another album's worth of songs demo-ed up, Dave's

first thought was to tell him to find another singer. Instead, he told him to send the

tapes over.

He was still thinking in those terms when Martin's package arrived. He picked up the pile of lyrics that accompanied the songs. The first track was "Condemnation." It was like nothing Martin had ever written in the past: soaring, majestic, beautiful. "It was a total relief! I couldn't believe it! I wish I could have written it."

Dave turned to the next page of lyrics-then dropped them in shock. Even in rough demo form, the next song was electrifying, a tightly coiled blues groove that built and burned. It was "I Feel You". The only reason he'd considered leaving Depeche Mode was because he couldn't ever see them matching his dreams. "I was ready to do, something with a purpose, and suddenly things started to fall into place."

Alan was already in Madrid, renting a private villa for the rest of Depeche

Mode to share, and organizing a temporary studio there. Dave and Teresa flew out there in

March, but even as the couple greeted Alan, Martin, and Fletch, the magic was dissipating.

By the time Dave had finished explaining the direction in which he saw the new album

progressing, he was ready to simply fly back to Los Angeles.

Alan was already in Madrid, renting a private villa for the rest of Depeche

Mode to share, and organizing a temporary studio there. Dave and Teresa flew out there in

March, but even as the couple greeted Alan, Martin, and Fletch, the magic was dissipating.

By the time Dave had finished explaining the direction in which he saw the new album

progressing, he was ready to simply fly back to Los Angeles.

"It was really traumatic," Dave described later. "There were lots of little struggles going on. Depeche Mode is a very English setup, and I came back [from L.A.] with a lot of aggressive influences, like, `I wanna do this, I wanna do that.' "

"I think Dave's very, very easily influenced, and I don't think that living in Los Angeles has had a good effect on him," Alan said.

Even the arrival of Daniel Miller in town, so often the oil that calmed

Depeche Mode’s stormy waters, did not resolve the conflicts. Neither did the

increasingly tempting nightlife of Madrid. Finally, Flood - drafted in to produce the new

album, but feeling increasingly useless as the arguments dragged unresolvedly on -

announced that enough was enough. It was time for this most unpartylike party to move, to

the Chateau du Pape in Hamburg.

Even the arrival of Daniel Miller in town, so often the oil that calmed

Depeche Mode’s stormy waters, did not resolve the conflicts. Neither did the

increasingly tempting nightlife of Madrid. Finally, Flood - drafted in to produce the new

album, but feeling increasingly useless as the arguments dragged unresolvedly on -

announced that enough was enough. It was time for this most unpartylike party to move, to

the Chateau du Pape in Hamburg.

And even that gap was lessening. It was Flood's idea to recruit Brian Eno to mastermind the inevitable program of remixes. And when Dave first suggested using live drums on the new album, and "bullied" Alan into playing them, Flood was as enthusiastic as Fletch was incredulous.

Fletcher said, `Dave's gone crazy, he wants drums,' " Dave said with a smirk. " `Next thing, he'll want backing singers.' And I did." Under Flood's guidance, the gospel trio of Hilda Campbell, Bazil Meade, and Samantha Smith was brought in for "Get Right with Me."

Neither was that the end of Dave's demands. A string

section, led by Will Malone, was recruited for the aching "One Caress"; Uileann

piper Steafan Hannigan was featured on "Judas."

Neither was that the end of Dave's demands. A string

section, led by Will Malone, was recruited for the aching "One Caress"; Uileann

piper Steafan Hannigan was featured on "Judas."

According to Alan, Flood's contribution was "the rare ability to step back and have a producer's perspective and also the technical know - how to be completely hands - on with all the equipment."

As much as Daniel Miller - who still stopped by the studio to offer advice, and who actively pushed the band to "try and break down ideas that were done before, and move forward, " Dave continued - Flood was now "a crucial member of our team."

Only as the sessions drew to a close, and Alan and Flood wrestled with the handful of loose ends that plagued each song, did that unity begin to splinter once again. A remix of "In Your Room," performed by Nirvana producer Butch Vig, was vetoed despite Dave's enthusiasm for the results.

"There was a bit of apathy from certain people," Alan detailed. "We couldn't agree about direction on a couple of songs, various things." He laughed. "We seem to have slipped into a cycle where we have to have a clear-the-air argument every few months."

One subject that the band did agree upon - or

threequarters of the band at any rate - was Dave and Teresa's forthcoming marriage, timed

for just weeks before the group went back on the road. Neither Alan, Martin, nor Fletch

was present at the ceremony.

One subject that the band did agree upon - or

threequarters of the band at any rate - was Dave and Teresa's forthcoming marriage, timed

for just weeks before the group went back on the road. Neither Alan, Martin, nor Fletch

was present at the ceremony.

The new album, dubbed-with a certain irony - ‘Songs of Faith and Devotion’ was proudly previewed by Alan as "very much a record for the Nineties."

"I Feel You" was chosen as the single that would preview Songs of Faith and Devotion, in February 1993. "Screeching unwillingly into patent robot throb," the song had a primal savagery that was wholly at odds with the introspective hopefulness that permeated the album, a vivid contrast that was only emphasized by Anton Corbijn's accompanying video.

Returning to the southwestern bordello theme of the "Personal Jesus" video, "I Feel You" was dominated by Dave's slow seduction by a writhing blonde - a seduction that concluded with Dave launching into a vaudevillian semi-striptease designed solely to give the maximum impact to the public unveiling of his new tattoos.

Songs of Faith and Devotion was released in early March 1993, crashing onto both the American and British charts at number one. It was the first truly "alternative" album ever to achieve so distinguished a double.

By the end of the summer of 1993, they had topped festival bills all over

Europe; by December, they'd headlined two of the biggest gigs London had seen all

year-their own Christmas extravaganza at Wembley Arena, and six months earlier, a massive

open-air show at the Crystal Palace Bowl.

By the end of the summer of 1993, they had topped festival bills all over

Europe; by December, they'd headlined two of the biggest gigs London had seen all

year-their own Christmas extravaganza at Wembley Arena, and six months earlier, a massive

open-air show at the Crystal Palace Bowl.

They were also celebrating another hit album, a track-by-track recreation of Songs of Faith and Devotion, recorded live around Europe and North America, and farther in both intent and execution than any Depeche Mode album before it. 'Songs of faith and Devotion Live' was accompanying with 'Devotional' concert video. Gone were the synth-driven textures of 101, or the album's worth of live cuts that had made it onto the B-sides of various singles.